This week we arrive at the last in a series of works that Peggy commissioned from esteemed choreographers in the early days of her solo company. Person Project was created for Peggy by NYC dancer and choreographer, Tere O’Connor.

“I first saw Tere O’Connor in a concert of Rosalind Newman’s work at Movement Research in lower Manhattan. The dancers were wearing practice clothes and Tere had on a kind of loose knitted shirt with sleeves that fluttered a few inches below his fingertips. His dancing was precise and delicate, organized according to an inscrutable logic. His gaze was cast downward, or perhaps inward, and I could not take my eyes off him.

At Danspace I encountered him in his own work – the duet Boy, Boy, Giant, Baby with Nancy Coenen – and was thunderstruck by his images and by the thud of realization that dropped for me. Tere also saw me perform (he sited Lar Lubovitch’s Exultate Jubilate) and one day he waited for me after a class I was teaching, introduced himself, and asked if I would dance for him in a quartet project, The Organization of Sadness. With hindsight, I understand how the androgyny of my body and my lack of femininity as a dancer made me a good choice in terms of supporting an underlying premise in his work — the disruption of expectation for conformity around gender expression.

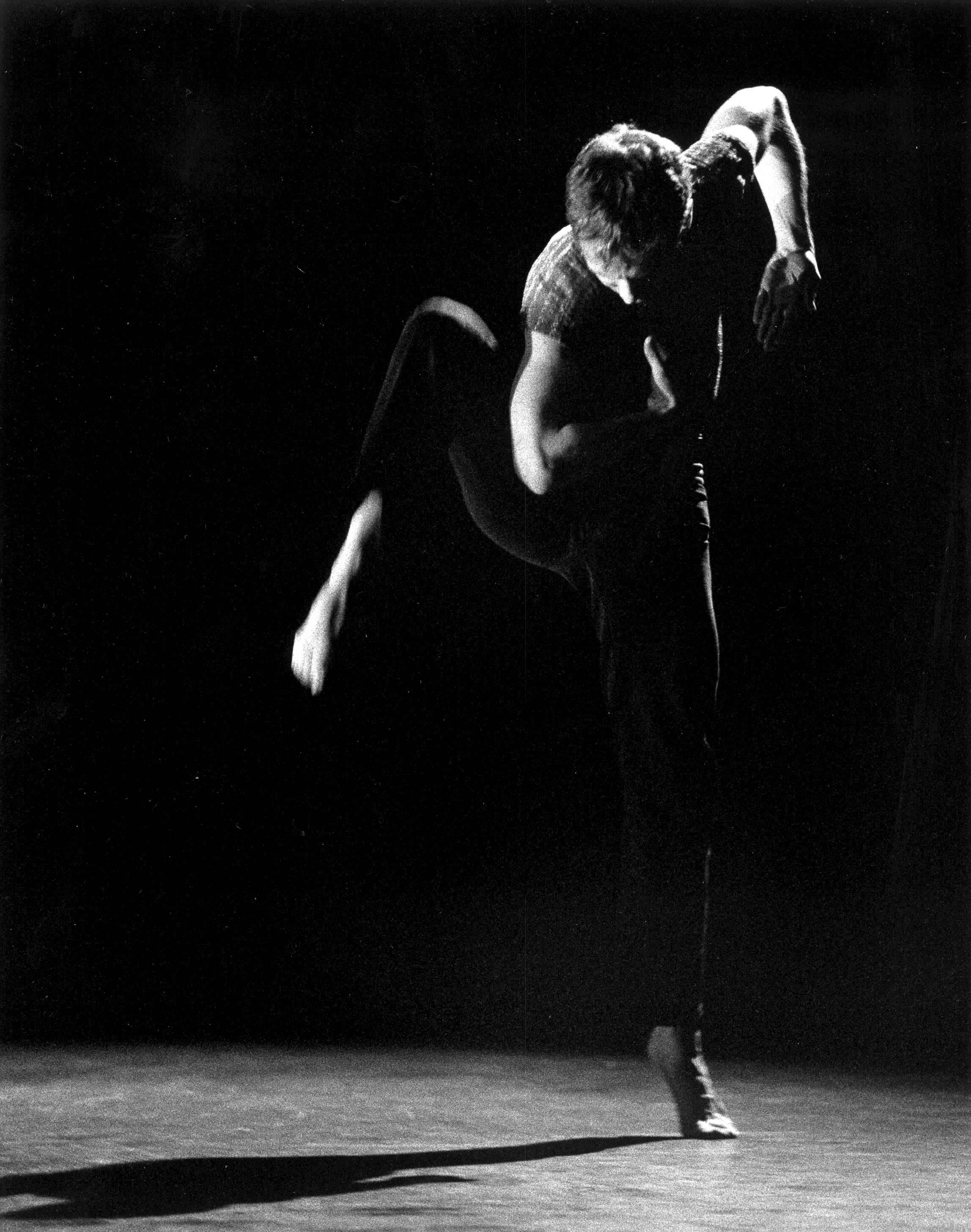

Tere made Person Project for me in 1991. At Unique Clothing on lower Broadway I tried on a succession of vintage dresses, and Tere and Nancy chose a red velvet party dress lined with stiffening buckram. The bodice was hard and flat and the skirt made a tremendous whap folding in on itself with every spin. Person Project is 20 minutes long and performed in silence until the very end, so the dress provided a kind of percussive accompaniment. I made very detailed notes on the inner workings of the dance that tracked the shift of states and emotions in order to keep the momentum of the dance moving forward without the markers of a soundtrack to navigate the way.

Tere is an absolute iconoclast in an art form in which an alignment with trends in form and content often determine success. Working within the medium of choreography he also pushes against it. His dances involve precise imagery and motions, but they are also a working-out-of-things through investigation, accident, self-correction, and erasure. I count myself extraordinarily fortunate to have worked with him.” PB

Tere writes about this time in the early 90s: “I was a young artist when I met Peggy Baker and asked her to dance in my work. I remember being gobsmacked the first time I saw her dance. I then got to meet this unique creature who was an icon for me, but also very available and most importantly, thoughtful. The work I asked her to be a part of was only the second dance I had made with other performers in it! I did not know what I was doing yet as a choreographer. I knew what I was attempting to move away from and I knew that I was in a state of experimentation; not looking for manifestoes, or aesthetic proclamations, just a way to work that included my intuition about the form. I was in this process of questioning dance. Peggy entered that realm unflinchingly, like an open book. She graced The Organization of Sadness with her presence and placed trust in me. She put her incredible body and mind to work right next to my queries and it was a joy. This early support from such an intelligent, venerated dance artist contributed greatly to my confidence in choosing more anomalous pathways as I forged my choreographic imprint.

One does not arrive at any substantive knowledge before working for a good while, and I was in a process of parsing out assumptions around gender, virtuosity, musicality and presence in dance, seeking to individuate beyond the default settings of western dance history. I was looking for an expressive vehicle for the capaciousness of persona and an internal life. Choreography seemed to be a perfect container for the ever-changing dynamics of consciousness. As a queer artist, I had understood early on that the facade of a person and their internal world are rarely indicators of each other. So much of what is roiling underneath is held hostage by the requirements of facing other humans.

When I created Person Project for Peggy, I wanted to start by finding a generic human presence and then build a person and an internal world with great variations. I did not, however, want it to etch a visual mark on the surface of the work. Perhaps inspired by performers like Liv Ullman or Isabelle Adjani, two extraordinarily subtle actresses of the day, I felt Peggy’s uncanny ability to electrify her dancing with emotionality was a perfect building block. She successfully avoided the all-purpose, melodramatic grimace, so common in dancers at that time, to create an internalized performance with compelling contrasts of emotion. The being who inhabits this dance engenders great tenderness. It is a person who is perhaps driven by unnamed emotional territories. Her masterful performance was so subtle, and so deeply poignant.

Peggy Baker’s magnanimous presence in my life helped launch me into an unapologetic exploratory process that has not left me to this day. Her early support for my work holds inestimable value as an initial generator for my career, one blessed by other such benevolent people along the way. I am so grateful to Peggy Baker and so astounded at everything she has accomplished as an artist–and a person.“ TO

"You can sense the compulsive quality of the movement - the pushing, pulling, opening and shutting of the body (and spirit); the effort and concentration required to set its directions." - Alina Gildner, The Globe and Mail

For more information about Tere O’Connor’s and the theme of ambiguity in his work, visit Classical Voice here.

For a fun look at the history of the vintage clothing scene in New York, visit racked.com here.