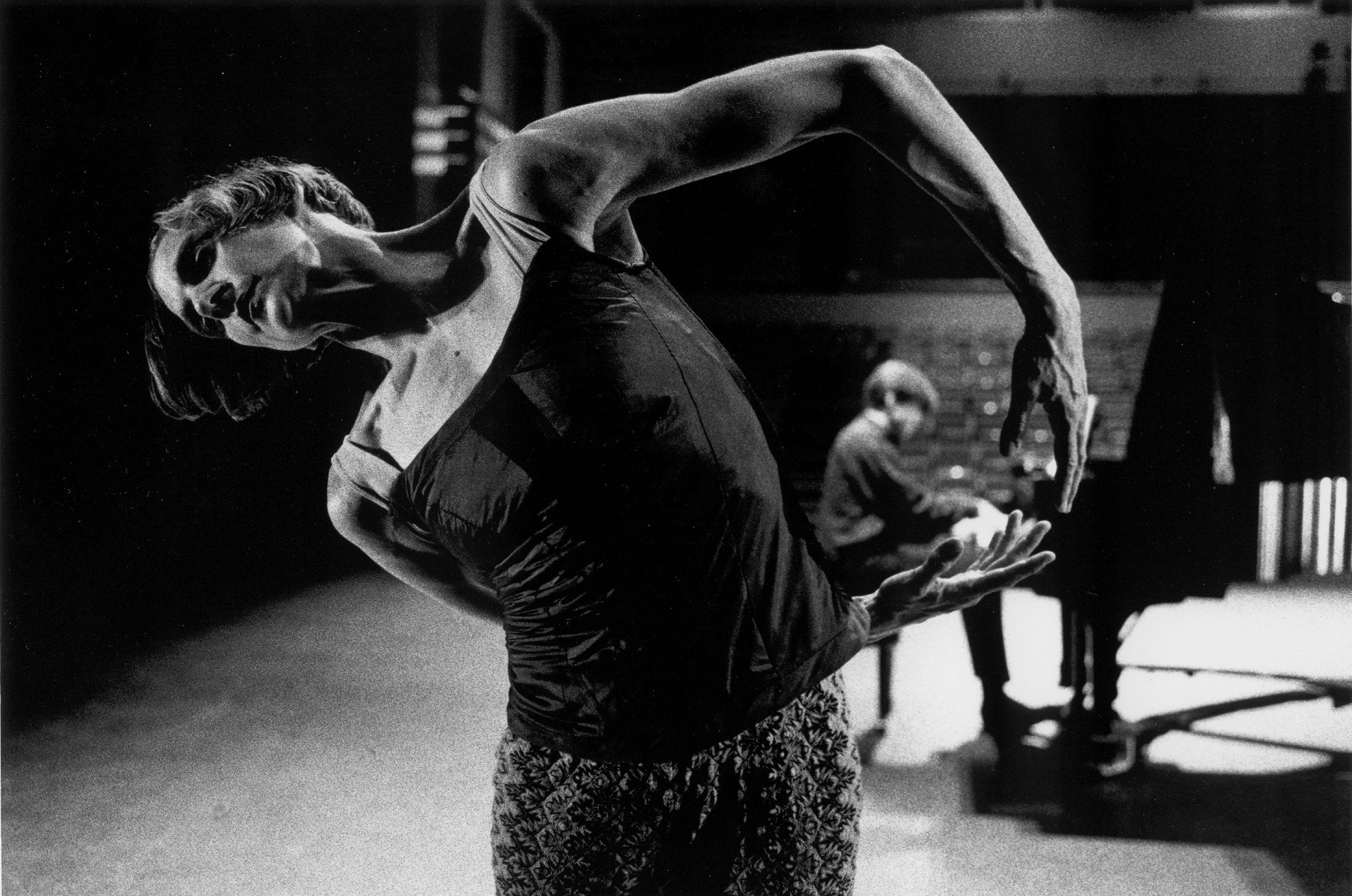

Unfold (2000)

/In 2000, the decade-long collaboration between Peggy Baker and Andrew Burashko sees them tackle a major new work suggested by Andrew: Aleksandr Scriabin’s 24 Preludes, Op. 11. Peggy writes:

“Andrew had been proposing this work for some time, and the gift of commissioning funds from Symphony Space in New York and the National Arts Centre in Ottawa – with performance dates that fell just a month apart – provided the perfect opportunity for us to dedicate ourselves to the development of this demanding work.

Like Chopin’s 24 Preludes, Op. 28, (which served as his model), Scriabin composed a short work in each of the major and minor keys of classical western music, and despite this academic premise, his 24 pieces are charged with deep emotion. Some sound as though they are at a loss to complete themselves, while others give the impression that they are about to float apart, combust, collapse inward, or dissolve. A couple of them are as conclusive as a slammed door at the end of a heated argument. Taken as a group they propose what I can only describe as a self-portrait of the composer, and any pianist taking them on must transcend their highly personal specificity and bring a singular interpretation to the score.

I wanted to step up to the score on these same terms, discovering within the style and scope of the music a framework within which to reveal myself with immediacy and authenticity. Ultimately, Unfold offered the audience an intimate experience of Andrew and I as individual artists and as artistic collaborators, but also simply as very different people who have built a deep friendship by bringing our worlds together.

Unfold falls half-way through the 20-year arc of my shared performance life with pianist Andrew Burashko and looking back I see that this was the last of my choreographic works to be created with him; the new dances that followed for he and I were the work of others – Doug Varone, James Kudelka, and Molissa Fenley.” PB

“Baker’s angular, constructivist choreography seems a part of the music, another instrument playing the melancholy themes. Sometimes she dances in silence… Sometimes Burashko plays alone. In those passages the ghost of the music and the after-images of Baker’s movement are ever-present.” - Susan Walker, The Toronto Star

If you’re looking for any information on Aleksandr Scriabin, the Scriabin Association has you covered and then some.