Heaven (2003)

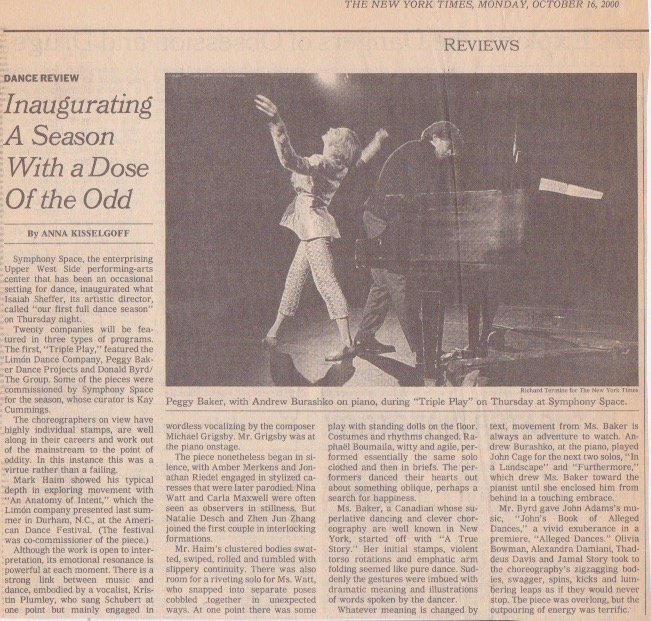

/This week we continue to look at a rich period before and after the turn of the millennium, during which Peggy worked with master choreographers from across Canada and the USA. We’ve arrived at the creation of Heaven for Peggy and pianist Andrew Burashko by award-winning NYC-based choreographer, Doug Varone.

Peggy writes: In 2003 Doug Varone brought together a quartet of dancers for a concert at Jacob’s Pillow titled Short Fictions. Esteemed Limon dancer Nina Watt, Varone Co. veteran Larry Hahn, and I were all in our fifties – with Doug not far behind – all of us baby-boom dance-boomers crossing a fifth decade threshold that had been extraordinarily rare in the previous generation. The program opened with Four Piano Pieces, the first three all Varone masterworks – Nocturn (Chopin), Aperture (Schubert), and Short Story (Rachmaninoff) and it closed with a new work for me with pianist Gabriela Imreh, Heaven, to Cesar Franck’s Prelude, Fugue and Variations.

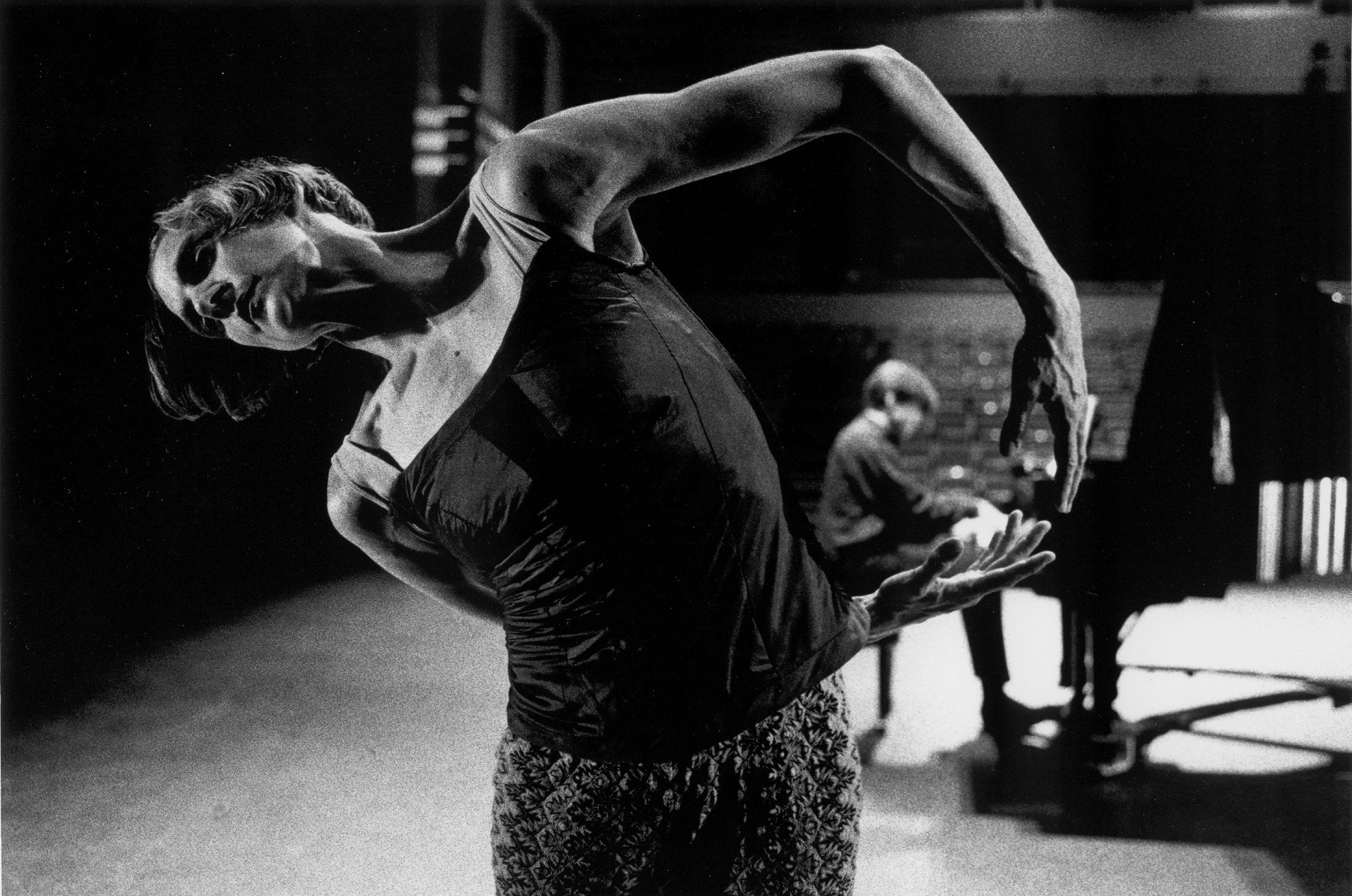

Heaven is kind of memory play in which the pianist and the dancer each seem to be alone remembering the other. I push against the piano, lean into it and stroke its surfaces. At one point I withdraw the stick holding the piano’s lid open and it slams closed. I sit on the bench back-to-back with the pianist; take their shoulders in my hands and move them; touch their head; lift their hands from keyboard; and even play some of the notes myself. The disruptions to her physical rapport with the piano were, understandably, unsettling to Gabriela, and the tensions provoked became central to the experience of the performance and to the images and associations that arose for the audience.

From the outset, Heaven was intended for my own repertoire, and Doug created it with Andrew Burashko and I. I remember us working in a New York studio with Andrew playing an upright piano with a table set against the side edge of the keyboard so that I could approximate movements against, along, and over it. Andrew was not thrown off at all by the extent and frequency with which the choreography implicated him. The one exception was when I played notes of the music, and due to his precise ear, my touch and timing required on-going coaching.

This work, with its evocations of absence and longing arising from music, holds in it the essence of my experience now, in hearing the music I once lived in as a dancer. - PB

For Facebook people, watch the performance of Heaven in full here on the Art of Time Ensemble Page.

Doug Varone’s Aperture can be seen on Youtube here and Short Story can be viewed here.