Piano Quartet (2012)

/Having created three works to piano music by John Cage – In a Landscape, Why the Brook Wept, and furthermore – and with a deep appreciation of his tremendous influence on the development of western music forms, Peggy marked the 2012 centenary of Cage’s birth with a new work in his honour. Peggy writes:

Immediately following its publication in 1996, I began working my way through the dense and stimulating MUSICAGE: Cage Muses on Words Art Music (John Cage, Joan Retallack). Cage had died four years earlier, and this book documented an extraordinary series of in-depth interviews in the last months of his life during which he reflected upon the full breadth of his artistic endeavours. Among countless pleasures, this book provided my first encounter with Cage’s poetry. More than any other writing I know, Cage’s poems (he calls them mesostic texts) feel to me like choreography – in the way that a single idea is pulled apart and reconfigured over an expanse of time, moving beyond the explicit language employed to call up images and juxtapositions that emerge, transform, catalyze and dissolve.

As the centenary of Cage’s birth approached, I began experimenting with his mesostic texts as the basis for movement scores. The process was instantly exciting and generative, so I began listening in earnest to his many works for prepared piano. Commissioned to create a brief solo for dancer Brian Lawson, I chose Cage’s Music for Marcel Duchamp, composed in 1947, and the beauty and fascination I found in that first dance led directly to the decision to tackle Cage’s epic Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano.

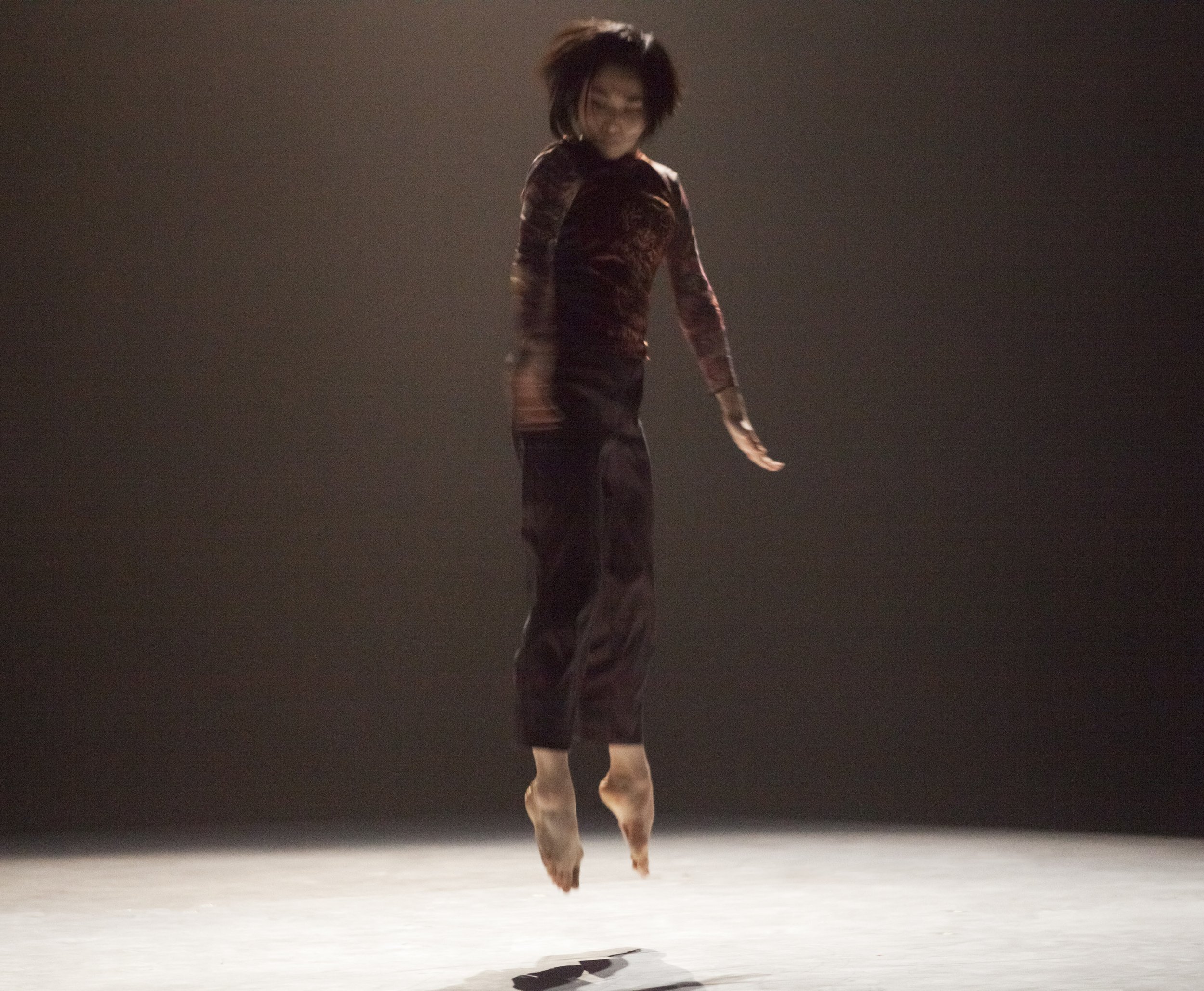

Piano/Quartet arose through that foundational solo for Brian Lawson (who worked alongside Sahara Morimoto); through subsequent choreographic research during two residencies in Philadelphia (Dance Advance, Pew Centre for the Arts and Heritage / Bill Bissell, director) involving dancers Gregory Holt, Bethany Formica and Shannon Murphy, and ultimately through intensive work with dancers Ric Brown, Sean Ling, Andrea Nann, and Sahara Morimoto.

Caroline O’Brien created a sensational wardrobe that allowed the dancers to switch up costume pieces for each scene; Marc Parent devised a gorgeous and eventful lighting design; and the production was completed with a series of beautiful, painterly projections by Larry Hahn. Upstage centre seated at a grand piano, completely unflustered by the flashing changes in the lighting and projections, and by the rustle, footfall, heavy breathing and constant movement of the dancers, pianist John Kameel Farah gave an astonishing series of virtuosic performances of some of the 20th Century’s most challenging and daring music. PB

“…mesmerizing…Epic in scope, inventive in structure and emotionally nuanced…” Michael Crabb, The Toronto Star