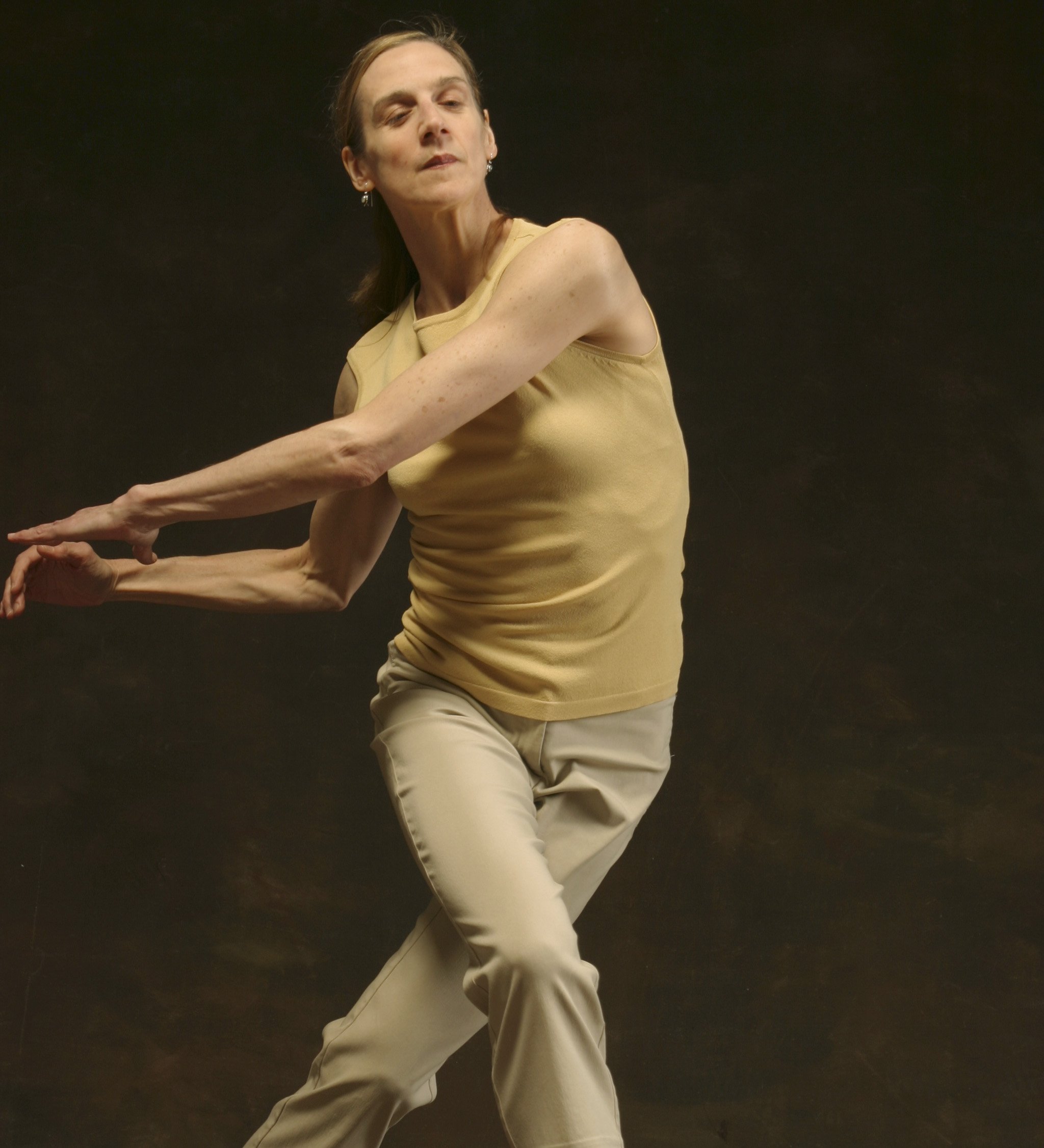

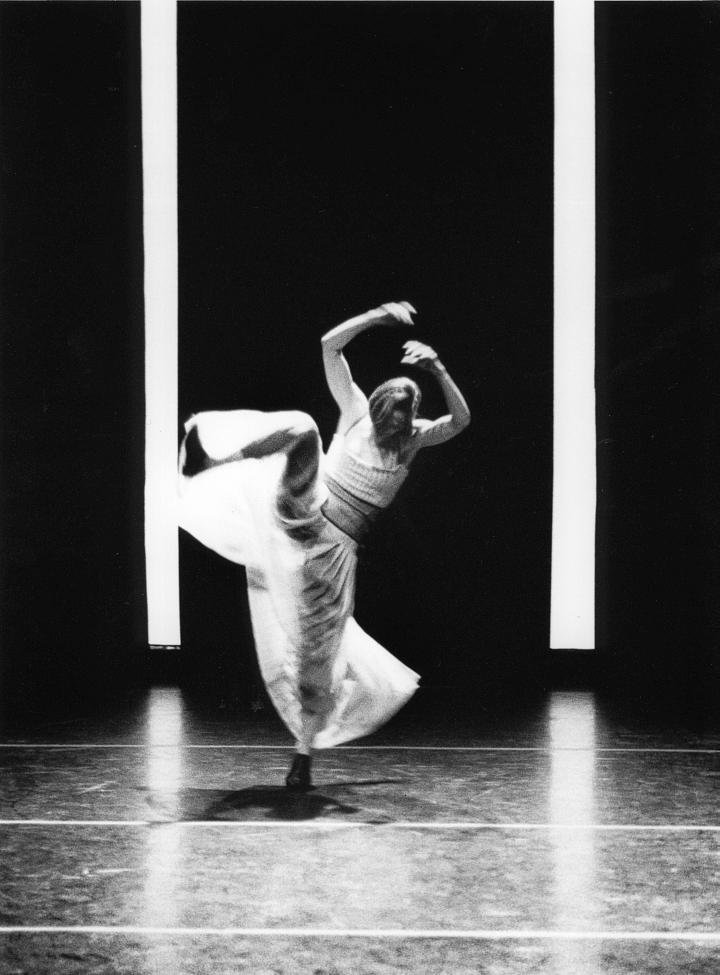

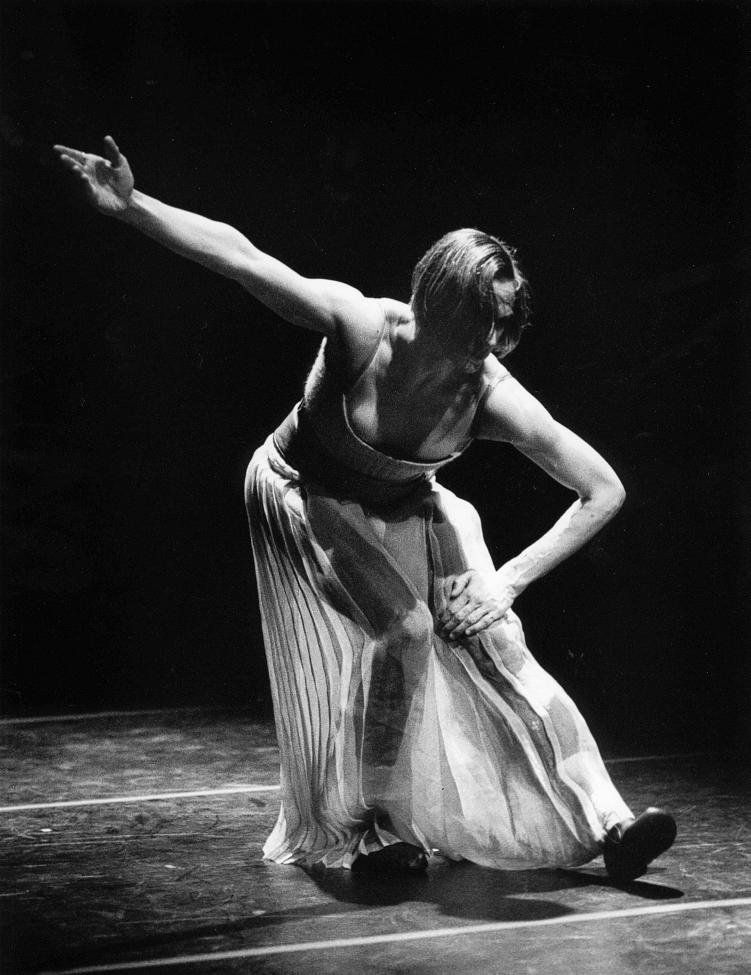

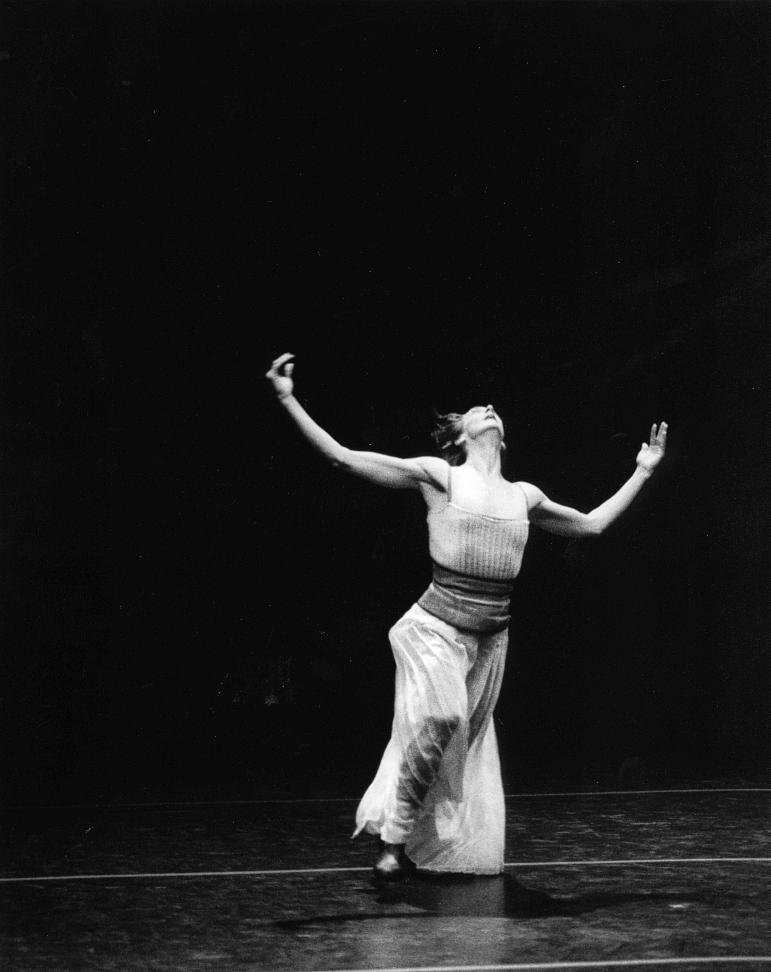

unmoored (2018)

/This week we hit the final solo that Peggy commissioned for- and performed- herself. A sequel to a work she premiered 14 years previously. Peggy writes:

In 2003 I turned to the extraordinary dance artist Sarah Chase to make a work for me. Sarah creates in a genre she describes as dancestories, and prior to working together she set me the task of writing two stories for every year of my life. When the time came to go into the studio together, I told Sarah that there was one aspect of my life that I hadn’t written about and could not share in the public sphere. Sarah agreed to my caveat, and we went on to create a very beautiful work titled The Disappearance of Right and Left. More than a decade later I went back to Sarah to let her know that I was now ready to think back on the events that I had previously held apart and to mindfully look to those events as the basis for the creation of a new dancestory.

In March of 2017, I sat down at a desk, in a small room, in the Bogliasco Foundation villa, where I was undertaking a 5-week fellowship in Italy. Guided by Jane Hirschfield’s extraordinary book Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry , I wrote down the stories I had not been previously ready to share. At the end of my residency I arranged the stories in a rough performance draft – incorporating some initial movement devised by Sarah – and shared the in-progress work that included a poem by Rumi as the final scene, with the other Bogliasco Foundation fellows.

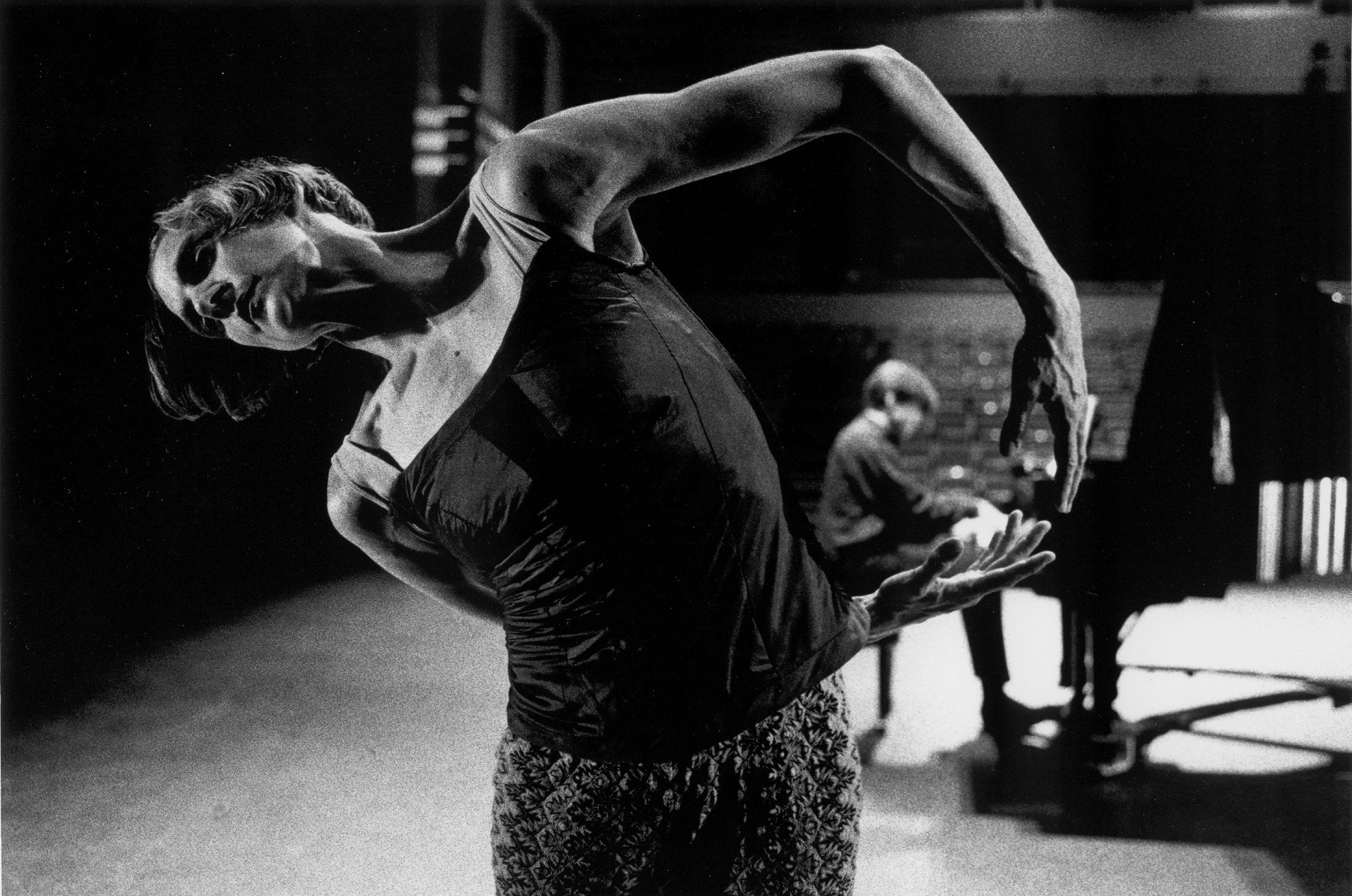

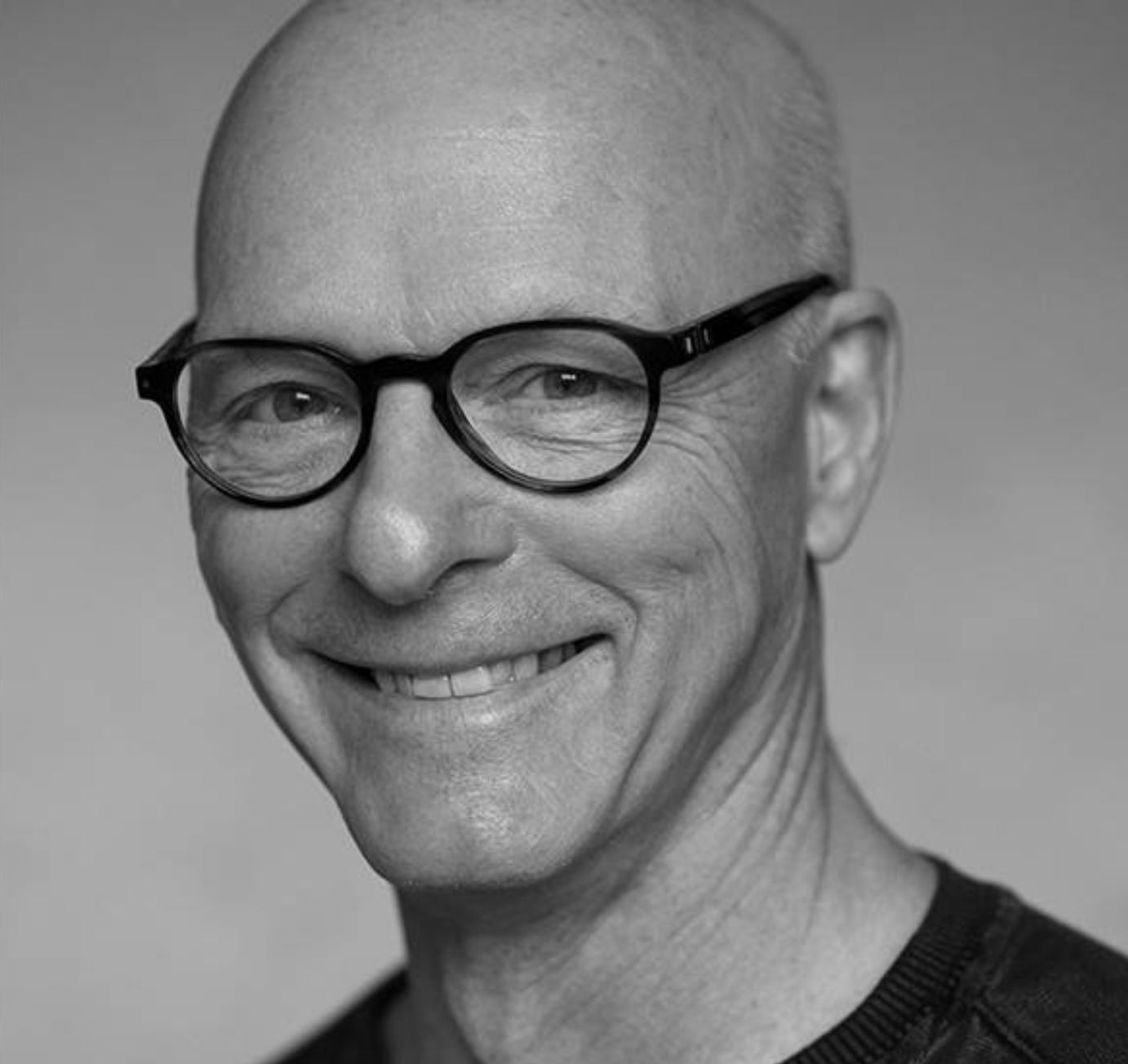

In the months that followed, Sarah and I worked together to develop a choreographic staging to frame and hold a distillation of my writing as a dancestory titled unmoored. The episodes that I recount in unmoored describe events during the 20-year arc of my marriage to the musician, composer, and disability rights activist, Ahmed Hassan. The complex and emotionally charged themes of disability, caregiving, and death at the heart of this work are handled by Sarah with tremendous sensitivity.

One of the poems included in Hirschfield’s book struck an especially deep chord with me. This poem by the 13th century Japanese Zen master Eihei Dogen captures something essential about the utter emptiness of loss, and of how that empty space can in fact offer an opening for illumination:

unmoored

in midnight water

no waves, no wind

the empty boat

is flooded with moonlight

In addition to the Bogliasco Foundation in Liguria, Italy, unmoored was created with the invaluable support of residencies at Tiamat House on Hornby Island B.C., (through the generosity of Judith Lawrence); and Ottawa Dance Directive, Artistic Director Yvonne Coutts / Associate Director Lana Morton.

unmoored premiered at The Theatre Centre in Toronto, with subsequent presentations at The Citadel (Toronto), EDAM (Vancouver), ArtSpring (Salt Spring Island B.C.) Crimson Coast Dance (Nanaimo), and Ottawa Dance Directive.

Winner - Dora Mavor Moore Award for Outstanding Performance in a Dance Production: Peggy Baker

“The work is one of total perfection as the heartbreaking text and Baker’s eloquent movement swing back and forth between darkness and light. “ Paula Citron

“Chase has shaped a performance that Baker speaks, sometimes reading, sometimes reciting, raw in its emotion and polished in its performance. As an artist, Baker needed to make this dance story, for it marks the renewal of creativity, going forward with undying love on the wings of Rumi.” Susan Walker

All photos below of Peggy Baker by Aleksandar Antonijevic.