Dreaming Awake (2008)

/In this week’s post, we look back at the third collaborative project with NY-based dancer and choreographer, Molissa Fenley.

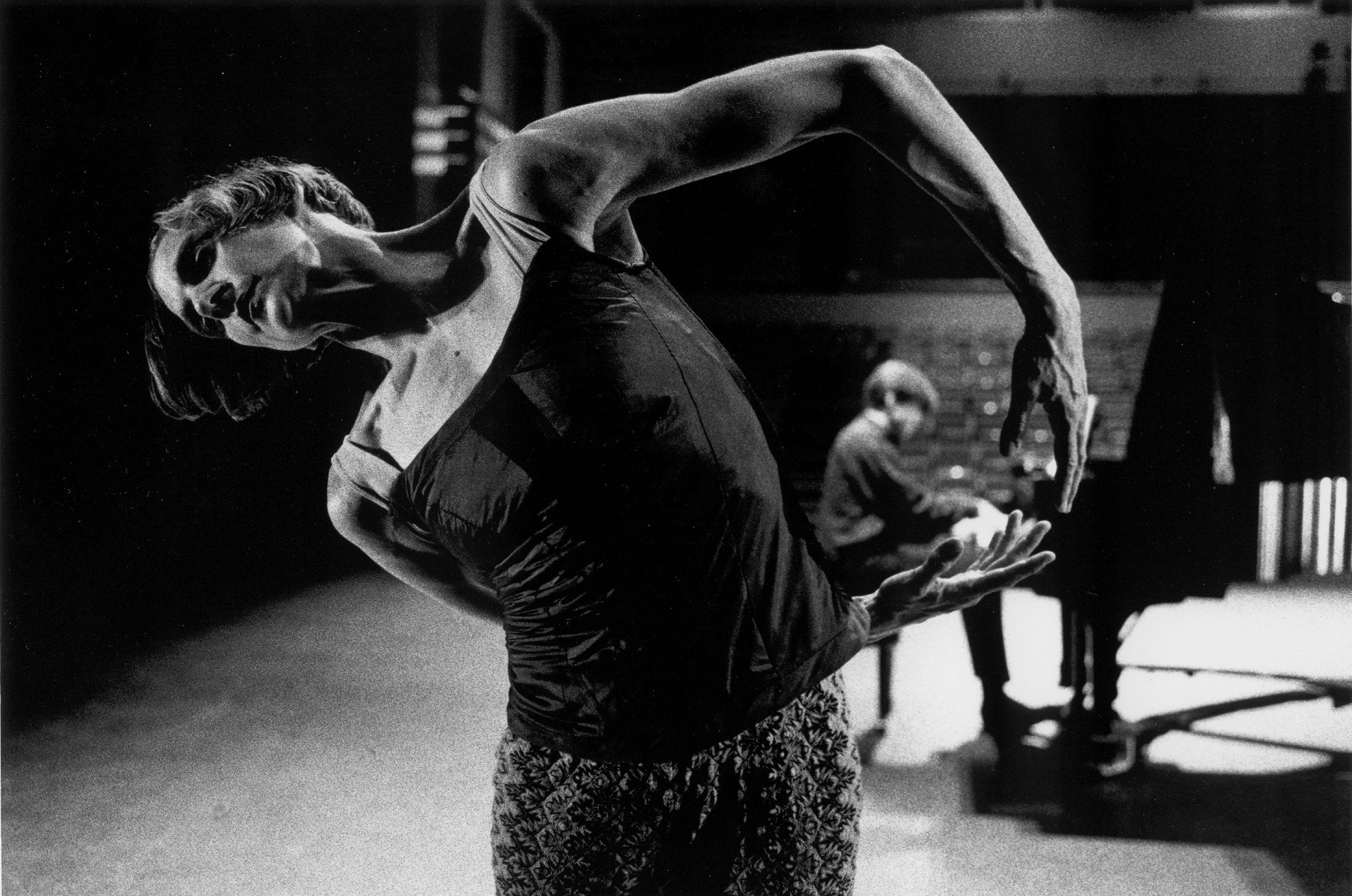

Peggy writes: I was extremely excited to be working with Molissa Fenley again when we set out on the development of Dreaming Awake with a premiere expected early in 2007. I had always taken a huge amount of pleasure in the circuitous choreographic pathways of her dances and the ways in which she connects with musical landmarks, with the dancer navigating the architecture of the sound rather than the phrasing of beats. Dance adrift on an ocean of music.

For Dreaming Awake Molissa had chosen a piano work of the same name by Phillip Glass and used the music – which cycles in repeating loops – twice in a row. It was an interesting coincidence because I had chosen to do the very same thing the previous year with Karen Tanaka’s score for Krishna’s Mouth and I fully appreciated Mo’s desire to double it up.

Choreographically, Molissa set out a series of complicated phrases in what proved to be a first iteration, because before long the phrases were fragmented and rearranged many times over, sometimes doubling back to places on the stage and within the choreographic language that were maddeningly familiar. It felt something like being inside of an architectural construct by Escher and it was quite disorienting. In an early studio showing I became hopelessly lost when I discovered myself at the same intersection in the dance several times in a row, an experience I found completely unnerving.

While I was rehearsing Dreaming Awake I developed chronic pain in the third metatarsal of my right foot. It eventually proved to be a stress fracture, and I learned that it wasn’t going to get better unless I could stop altogether for many weeks. On the other hand, it had been hurting me for months without interfering with what I needed to accomplish, so I decided to go ahead with my planned 5-city tour (titled “3”) thinking that once it was finished I would take time off. Then, just days before leaving for Montreal, doing a simple transfer of weight to my right foot – (you’ve probably seen this coming) – I felt the bone snap and there was no longer any question about when I would stop so that the healing could begin.

Embarking on tour a year later, my foot was up to the physical challenge, but the complexities of finding my way through the labyrinth of steps in this gorgeous dance continued to threaten me with catastrophe. I finally premiered Dreaming Awake in Calgary, but that foot injury marked the beginning of slow shift in my thinking and eventually in my dance practice, one that led me to the role of choreographer of ensemble works.